Cookie was my Bar Grandfather

The Blue Star Buffet was the Cornerstone of My Childhood Saloons

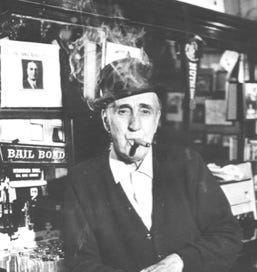

Cookie was my bar grandfather: kind, loving, and protective. He wore a black Homburg hat and nested a fat cigar in the corner of his thin lips every day of the year. He had warm brown Italian eyes, nestled in laugh wrinkles, and a big honker that matched his cigar. He always carried a handkerchief for it.

I grew up in Cookie's. The smoky bar was down the block from San Francisco’s old Hall of Justice on Kearny Street and was frequented by cops, perps, lawyers, bail bondsmen, baseball players, boxers, judges, mailmen, newspaper men, and cooks long after the hall was demolished and replaced with a Holiday Inn.

Cookie’s was the keystone in the constellation of the city’s saloons that my dad used as offices, living rooms, social clubs, and secretaries as he moved through his career as a reporter, editor, and publisher in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. To me it was like a grandparent’s living room: it could be in turns fun or boring but I always felt loved.

Often my father was there all afternoon and evening “working,” i.e. drinking, talking with sources, making calls in the wooden pay phone booth with the folding door, and writing notes on cocktail napkins or on one of his yellow legal pads.

“Hinckle? Haven’t seen ‘im,” was Cookie’s pat response when anyone called the bar looking for him. He was the keeper of many secrets.

Dad kept a spare typewriter there and would sometimes pound out his story on one of the little cafe tables along the wall and then dictate it to the San Francisco Chronicle copy desk from the wooden phone booth, squeezing his 6’1” frame and scoliosis hump inside to pull the folding door closed if they complained they couldn’t hear over the noise.

Cookie watered his booze down so much that you couldn't get drunk there if you tried, dad always said. His business card was tiny, a unique 2” by 1” number that read:

The Blue Star Buffet

708 Kearny Street, San Francisco

Laurence “Cookie” Picetti, Proprietor

The Biggest Water Bill in Town

The Blue Star Buffet had a narrow, arched doorway of cobalt blue glass tiles dulled by the grime of leaded gas exhaust from the buses and cars roaring through Chinatown on their way to North Beach or Fisherman’s Wharf.

It had one of those classic saloon horizontal split doors that allowed some fresh air and light into the joint from the waist up. Inside, it was narrow and vertical, with soaring 18-foot ceilings relieving its tight 12-foot width, half of it taken up by the bar.

If the bar wasn’t busy, Cookie would let me and my little sister Hilary press the stiff brass buttons that popped out the wooden cash register drawer with a loud DING that delighted us. Behind it was a framed black and white photo of Cookie and his wife Margie on their 20th anniversary. On the huge wall above the bar was a giant line drawing of an Italian woman leading a donkey. Cookie would say, in his perfect San Francisco Nasal accent, that the woman was Margie and the ass was him. “If id wasunt fer her, Iduh bin a bum.”

Cookie was born in North Beach and his Genovese father had been a garbageman. Cookie ran dice games on the waterfront and worked for bail bondsmen before getting in the saloon business. His grandmother had nicknamed him “cookie” after he was found eating cookies on Stockton Street after the 1906 earthquake.

Next door was a Chinese-American diner that was connected inside to Cookie’s by a swinging door in the wall after the end of the bar, hence the “buffet.” You could get a pretty decent plate of chop suey or a burger, by 1970s standards, delivered into the bar. But no one came there for the food.

My mom would park our white 1969 Impala convertible and hold our hands as we crossed the busy roadway. My dad would be standing at the bar (only women and piles of newspapers should sit on bar stools, he often proclaimed), one foot on the brass rail by the floor, usually deep in conversation with someone—a source, an artist, a conspiracy theorist, a private detective or a cop—or playing Liar's Dice. Sets of brown and black leather dice cups, lined in red or green felt, were kept behind the bar and Cookie would pull them on request to settle a wager or decide who would buy the next round.

Cigars, cigarettes, and the occasional pipe had dimmed the formerly-white ceiling with the residue of a million exhales. I remember my eyes being riveted on a woman’s elegant Virginia Slims cigarette as my dad lit it for her. He never smoked, except the occasional cigar. Cookie puffed about 20 Corina Westerns a day.

On the walls were framed photos of Seabiscuit, Muhammad Ali, Babe Ruth, Joe Namath, local cop heroes and police captains, and a framed script excerpt beneath a photo of Dragnet TV stars Jack Webb and Harry Morgan,

"Where should we go for a drink?"

"Cookie's. Where else?"

Why do you drink in right-wing bars? Dad would get asked by lefty comrades in the 60s. “Do you know any good left-wing bars?” His retort usually settled the matter.

Cookie dropped everything when my sister and I came to visit. Immediately he would clear two bar stools for us and warn the patrons to watch their language. “Darez laidees prezent!" We’d watch him make our Shirley Temples (grenadine syrup, ½ 7-Up, ½ soda water, a maraschino cherry or two, and a short two-lane red plastic straw) and he would tell us about Margie or his granddaughter Debby, who was my age, and asked us about school.

Bar Time

There was a green spring water clock on the back wall next to the stairs, which was set to Bar Time (15 minutes fast) to help clear out the drunks. Above it was a large moose head with massive antlers and below it were stacked cases of bottled beer. The stairs led up to an alcove storage area above the bathroom. We would play up there amidst a dusty, but still scary, stuffed grizzly bear, assorted mounted deer heads piled on the floor, a broken cuckoo clock, busted wooden crates, and bar stools and chairs in various states of disrepair.

Up here, the blue haze of smoke was thick like LA smog and the sounds of the bar symphony drifted up through it: the soprano rattle of dice followed by the deep whomp of a leather dice cup on the bar; shouts of “Liar!” against the crescendo of keys and the slam of the big brass cash register drawer; ice cubes being corralled into five-inch-tall glasses with the hum of mens' voices punctuated by baritone guffaws or the the occasional high-pitched laugh of a woman.

We felt so at home here that once when my sister was on a 2nd grade field trip to historic Portsmouth Square across the street, she peeled off with a group of friends and brought them into Cookie’s. The worried chaperones found the missing little girls in the bar drinking Shirley Temples and chatting with Cookie.

Cookie always gave us each a silver dollar from the cash register. Sometimes we kept them for our piggy banks at home and other times, our parents would let us walk alone to the cigar store on the corner of Kearny and Clay, right next to the XXX dirty book store, and buy Ghirardelli Flicks chocolate. The chocolate disks would fall out of the dark blue foil-wrapped cardboard tube if you didn't fold the top right. If my mom brought Alice, our Basset hound, we’d take her with us to play in the park across the street if we got bored.

Cookie had a big glass jar, an empty industrial-sized former home of cocktail cherries or onions or olives, under the bar and if you got a parking or a speeding ticket, you could put it in the jar and it would get “fixed,” meaning a friend of Cookie’s would tear it up for you.

Here’s Dad writing about Cookie’s juice with the cops in a June 1980 column in the San Francisco Chronicle.

Cookie gave me my baptism into the real world of beneficent San Francisco corruption. One day in the early 1960s I walked into his bar with the sword of death visibly dangling over my head. “Whatsdamatter kid?” He asked me from behind a cigar without the benefit of moving his lips. I explained that I had only four hours to surrender myself at the Hall of Justice or an all-points bulletin was going out for my arrest on the charge of defrauding a merchant’s lien.

“Whosedaguy tryna arrest ya?” Cookie asked. I told him the name of the arresting officer. “Him? HE aint going to arrest you, for chrissakes,” Cookie said. “Why didnt ya tell him you was a friend of mine?”

With that, he dialed the phone, asked for the fraud detail and proceeded to more or less explain the situation by swearing at the person on the other end of the phone for presuming to arrest one of his customers.

Cookie handed me the phone. “Here, talk to him,” he said. I ventured a frail hello. “Hey, I didn’t know you were a friend of Cookie’s,” the inspector said. “Why didn’t you tell me that? Look, here’s what we’ll do. I got the blue copy of the warrant here, and I’ll go downstairs and lift the green copy out of the other file and I’ll rip them up. I can’t get the white copy out of the other D.A.’s office, but they don’t pay much attention to these kinds of things unless someone’s screaming, and Cookie knows a guy who can talk Sicilian turkey to the Italian and get this patched up before he starts bugging the D.A. again, so you’ll be okay. Okay?

I gratefully hung up the phone. Cookie was chomping his cigar. He took it out of his mouth and said, “You should get that guy a few bottles of Old Crow. That’s what he drinks.” I said I’d get the cop a case. Cookie gave me a look like I had just eaten his pet goldfish. “Three bottles is what I said,” he said. “You get him three. Any more and you’ll spoil the guy.”

When I left San Francisco for the first time in 1982 to head for college in New York, Cookie honked his 78-year-old nose in his handkerchief, wiped his eyes, and hugged me. He told me to study hard, be careful, and handed me a business card.

"If yuh ged inna trubble in New Yawk, you call this guy—day or night—and tell him Cookie sent you. He'll take care of it." The business card belonged to the head of the New York Teamsters.

Great piece! I'll never forget your father (and others) in blue and white striped seersucker suits at your wedding. Glad I found your stories here.

What a wonderful piece