Cold Water Curious?

A primer on the benefits and risks of cold water swimming

Shivering on the beach in the lashing wind, I cringe as the 53°F water of San Francisco Bay kisses my toes in the cold sand of Aquatic Park. Why do I do this? I ask myself. Why don’t I wear a wetsuit? What’s so great about swimming through winter?

I know the answer: I will feel amazing afterwards.

Every year when the water temperature drops below 55 degrees, I ask myself: am I really going to swim all winter? It’s going to be COLD, I whine to myself. For the last ten years, I’ve managed to swim through each winter. Last year, I swam in an icy lake in Vermont and found my body and mind could do more than I ever imagined.

Are you cold water curious? Have you ever walked by a beach and seen “those crazy people” swimming when you were bundled up and wondered what it would be like if you were brave enough to try? I’m here to tell you, if mere mortals such as myself can do it, so can you.

Cold water swimming is no joke. Myself, and plenty of other swimmers I know get very blasé about it, until someone gets hypothermic and then we are all reminded that it is an extreme sport that carries real risks along with its many joys and benefits. If you’ve never done it, I do recommend talking to your healthcare practitioner before you try, especially if you have any known heart or cardiovascular issues.

It is truly a wonderful experience and a welcoming community. Read on for the benefits, the risks, and how to try it safely.

The Benefits

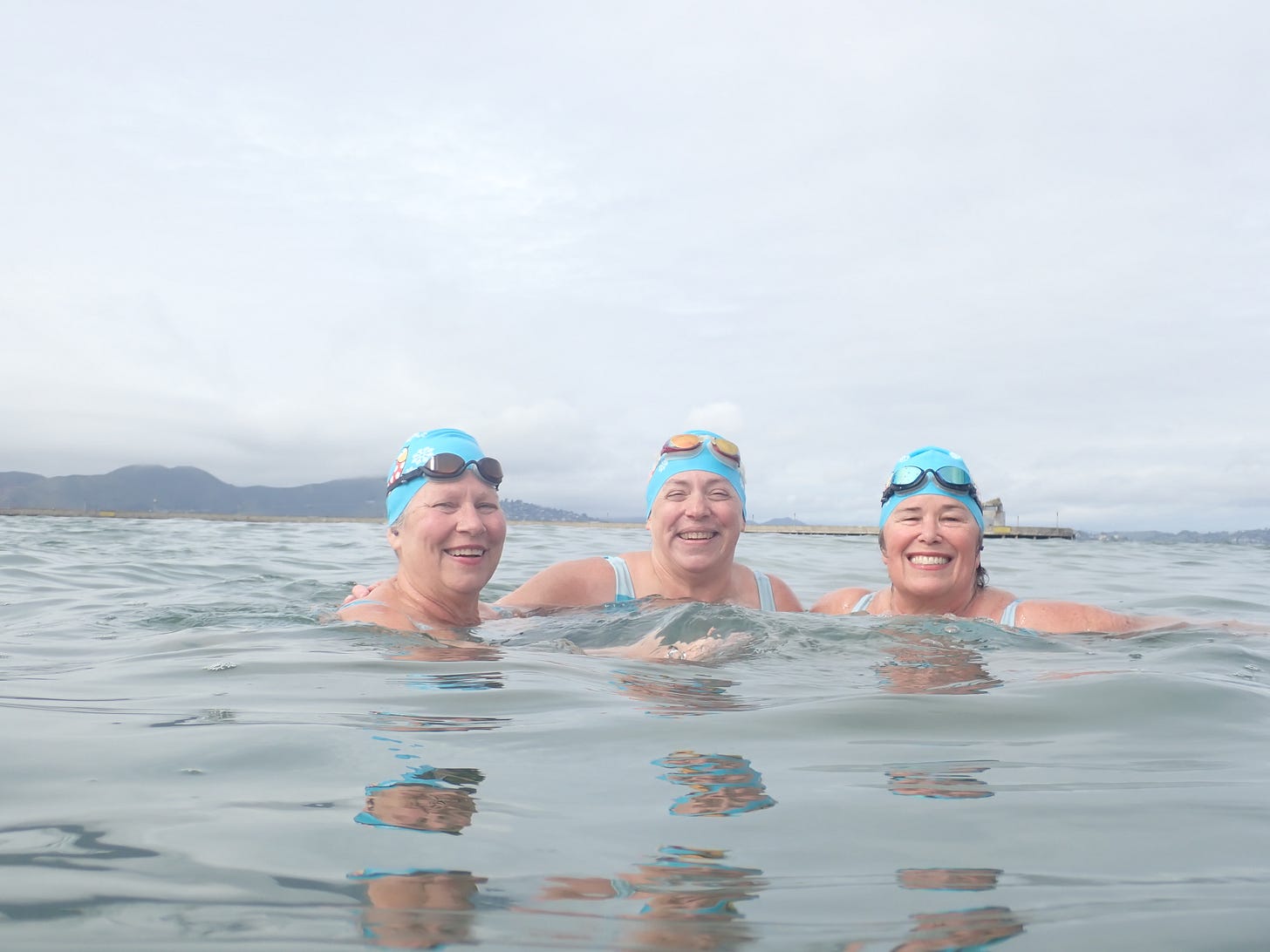

Open water or “wild” swimming—swimming in lakes, rivers, ponds, and oceans—has continued to increase in popularity since the pandemic, when many pool swimmers discovered its joys. Those seeking out cold water—loosely defined as water below 70°F—and “winter” or “ice” swimming—defined as water below 41°F—has grown as well, with Instagrammers, documentaries, and blogs inspiring others with their tales of recovery from depression and anxiety through cold water swimming. Whole communities of like-minded adventurers have sprung up, such as the Bluetits Open Water Swimmers, first begun by a group of women swimmers in Pembrokeshire, UK, in 2014, that is now a global movement.

Regular cold water swimmers all claim improved mood, reduced anxiety, better energy and circulation, and lower inflammation. Women especially report that cold water reduces their perimenopause and menopause symptoms. I have experienced all of these benefits and more. While few studies have been done on the exact physical health benefits, several promising ones have found improved general well-being and mental health—notably on its potential to treat major depressive disorder.

The Risks

Cold-water swimming is an extreme sport that requires training and caution. Along with its many benefits, there are real risks, including death, that all swimmers, rowers, kayakers, and boaters who play in or on it need to know. Cold shock is the body’s response to sudden immersion in cold water and causes uncontrollable gasping and hyperventilation, which can lead to drowning. There is also the potential for increased heart rate and blood pressure, which can lead to heart attack or stroke. According to the National Center for Cold Water, controlling your breathing becomes increasingly difficult in water below 70°F, and the potential for cold shock is an extreme life-threatening danger in water below 60°F.

The adrenaline rush produced by your body’s fight-or-flight response to cold water may also cause acute anxiety and even panic attacks, which can also increase your risk of drowning.

You should be especially careful if you have cardiac or respiratory issues (such as asthma) or high blood pressure. Discuss the risks with your doctor before you attempt your first swim.

How to Try Wild Swimming Safely

Start slowly and build acclimation (tolerance) through repetition. Limit your first cold water swim to just a few strokes and no more than 2–5 minutes. Don’t overdo it!

Go with a friend. Never swim alone, especially in cold water. If you don’t personally know anyone who can bring you with them, talk to local swimmers you see at known swim spots. Open-water swimmers are generally very welcoming to newcomers and knowledgeable about local conditions. Or do a search for a local wild swimming group. Always let someone know when you go for a swim and when they should expect you back.

Gear. Get a watch with a timer to monitor your time in the water. Wear whatever makes you comfortable. A neoprene wetsuit, booties, gloves, and a neoprene swim cap will keep you warmer; earplugs, if you submerge your head, will protect your ear canal from the cold; goggles will keep your eyes safe. A swim tow buoy improves your visibility and gives you a place to rest if you ever need it. Make it a party by bringing an emotional support swim buoy! I have two sizes! Bring a towel and layers of warm, dry clothes and shoes to change into afterward. A windproof swim parka or changing robe is a nice thing. Bring hot tea and a snack for post-swim.

Getting in. Before you go, check the weather, water temperature, and the tides, before venturing to a swimming spot. Have a plan and know where you will get in and where you will get out. Be well hydrated, fueled (have eaten), rested, and not hungover (alcohol impairs the body’s ability to deal with the cold). Stay dressed until you’re ready to enter the water—don’t stand around in your bathing suit in the cold air chatting. NEVER DIVE IN, as this will increase the risk of cold shock. Wade in slowly, letting your body adjust. Splash some water on your neck and face before submerging your chest or head to temper the cold shock. Stay at a depth where you can stand during your first swim and monitor your cold response. The water may feel painfully cold. You may hyperventilate or hold your breath. Your heart rate may soar and your brain will tell you to get out. EXHALE. Focus on calming your breathing. Look at the sky and the water—enjoy nature!

Limit your first cold water swim to just a few strokes and no more than 2–5 minutes. Don’t overdo it, get out when you feel like you could stay in longer. The Outdoor Swimming Society has a thoughtful equation for outdoor “swimming within your limits” and an Outdoor Swimmers’ Code.

Getting out. Monitor your time and get out before you think you need to—your body will continue to cool after you are out of the water. If at any point during your swim you start to feel warm and happy, you should get out immediately, as you are likely hypothermic. Your hands and feet may be quite numb, you may not feel sharp rocks and have trouble with zippers. Ask for help. Watch for signs of hypothermia (slurred speech, shivering, etc). Take off your wet suit and get into dry, warm clothes as soon as possible. Drink a warm beverage and eat something. Be aware of signs of the “after-drop,” about 10 minutes or so after you get out, when cooled blood from your limbs enters your core and further lowers your body temperature. This can cause you to shiver violently, faint, or cause heart failure. Warm up slowly, avoiding a hot-hot shower. Don’t drive or bike until you are sure you are thoroughly warmed. Enjoy the serene glow that the cold swim gave you. You have earned your bragging rights!

In spite of all the risks, done wisely, cold water swimming is a deeply satisfying way to merge nature with exercise and community. After thirty years of doing it, I can say it has taught me more about myself that any other experience in my life besides marriage and motherhood. No matter how much I ever dread getting in, I have never been sorry I took a swim. Be safe and enjoy.

Disclaimer: Cold water swimming is an extreme sport that can be life-threatening. Confer with your doctor before trying, and attempt at your own risk.

Such good advice! Love remembering Aquatic Park--so lovely.

For me, there's nothing like hiking and then jumping in a mountain lake, but yeah, I've experienced that cold shock loss of breath a couple of times. No fun. I'd rather not go below 65 or so. If I do, I'll try to remember your pre-splashing advice.