"The shark in an updated Jaws could not be the villain; it would have to be written as the victim; for, worldwide, sharks are much more the oppressed than the oppressors."

–Peter Benchley, author of JAWS

“It’s a shark movie. I think it will initially scare people and cause a great increase in aquaphobia next summer at all the beach resort areas.”

-Stephen Spielberg in 1974 when asked by Peter Benchley what kind of movie he was making out of his book.

I remember the girl stripping naked while running on the dunes and then diving into the ocean and swimming out in the twilight while the drunk guy she had been flirting with fell over as he tried to pull off his boots and passed out at the water’s edge. She was pretty. She had boobs, which I didn’t have yet at age 10 but was very interested in acquiring.

What happened next seared two things into me:

Sharks are in the ocean with one thing on their mind: eating humans.

Bad things happen to brave girls who leave boys to swim in the ocean alone.

I don’t remember which adult took me to see JAWS when it opened that summer of 1975. In all likelihood, I probably BEGGED to go. Everyone, including my parents, had read Peter Benchley’s novel and now everyone was going to see the movie directed by some young director named Stephen Spielberg. Plus, JAWS was about a shark and sharks lived in the ocean and I was already captivated by my simultaneous desire and terror to be on it, in it, and near it. I had almost been drowned by a sleeper wave on the Sonoma County coast when I was five years old, so I already knew the ocean could kill you whenever it wanted.

The nightmare I had for weeks afterwards: blood spewing from Quint’s mouth (played to a surly Captain Ahab T by Robert Shaw) as the shark crushed his torso in its mouth and dragged him off the Orca. I woke up in a sweat, heart-pounding to the beat of that sound, that bone rattling, Oscar-winning John Williams score: duh duh, duh duh duh duh dun dun duh duh dun dun duh duh, dudududuh! It remains the most menacing music I have ever heard.

The 50th Anniversary of JAWS

You can read elsewhere about why JAWS is still relevant on its 50th anniversary; the real 1916 New Jersey shark attacks that inspired it; how it both set the world against sharks and inspired generations of marine biologists; the film as an allegory for everything from predatory capitalism (Fidel Castro loved the book) to Vietnam and Moby Dick; the origin story of the “You’re gonna need a bigger boat” line (famously ad-libbed by Roy Sheider, who played the beachtown sheriff/reluctant hero trying to save people from the greedy mayor and the shark); everything that went wrong while using the ocean as a set for the first time in movie history and Bruce, the three mechanical sharks whose animatronics got fried by seawater.

The malfunctioning sharks necessitated hiding it underwater for most of the movie. Our imaginations filled its absence with our personal monsters. Our fears of the Unknown. The Other. The Irrational. The Invader. The menace to orderly life. Chaos. Of being bitten. Being eaten. Taken in the mysterious ocean.

JAWS for Swimmers

For swimmers, JAWS changed everything. People who’ve watched it (even now) report becoming afraid to be in water, even bathtubs and swimming pools. I don’t remember being afraid to swim afterwards, but I didn’t want to play JAWS in the pool until a few years later.

Today when I tell people that I swim all year in San Francisco Bay, the first question I get asked, thanks to JAWS and its modern children Shark Week, Sharknado, The Meg, etc., is:

“What about the sharks? Aren’t you worried?”

Yes, I answer, but mostly not. If you’re yoked to the ocean like I am, you find a way to educate your fear even if it takes years. The panic attacks I had while swimming in my thirties no doubt had roots in the primitive brain that wants to be safe from cold and predators. But I kept trying because I loved it. Little swim by little swim, year after year, I retrained my nervous system to tolerate both the cold and the idea that I’m a visitor to sharks’ home.

I Wanted to be Hooper

When I saw JAWS, I wanted to be Hooper, the ichthyologist from the marine institute. The brave, smart, and funny scientist; the rational shark researcher. I went on to study marine science, oceanography, nautical science, and marine mammal biology in high school and college. I sailed on tall ships studying humpback whales off New England and sperm whales in the Caribbean.

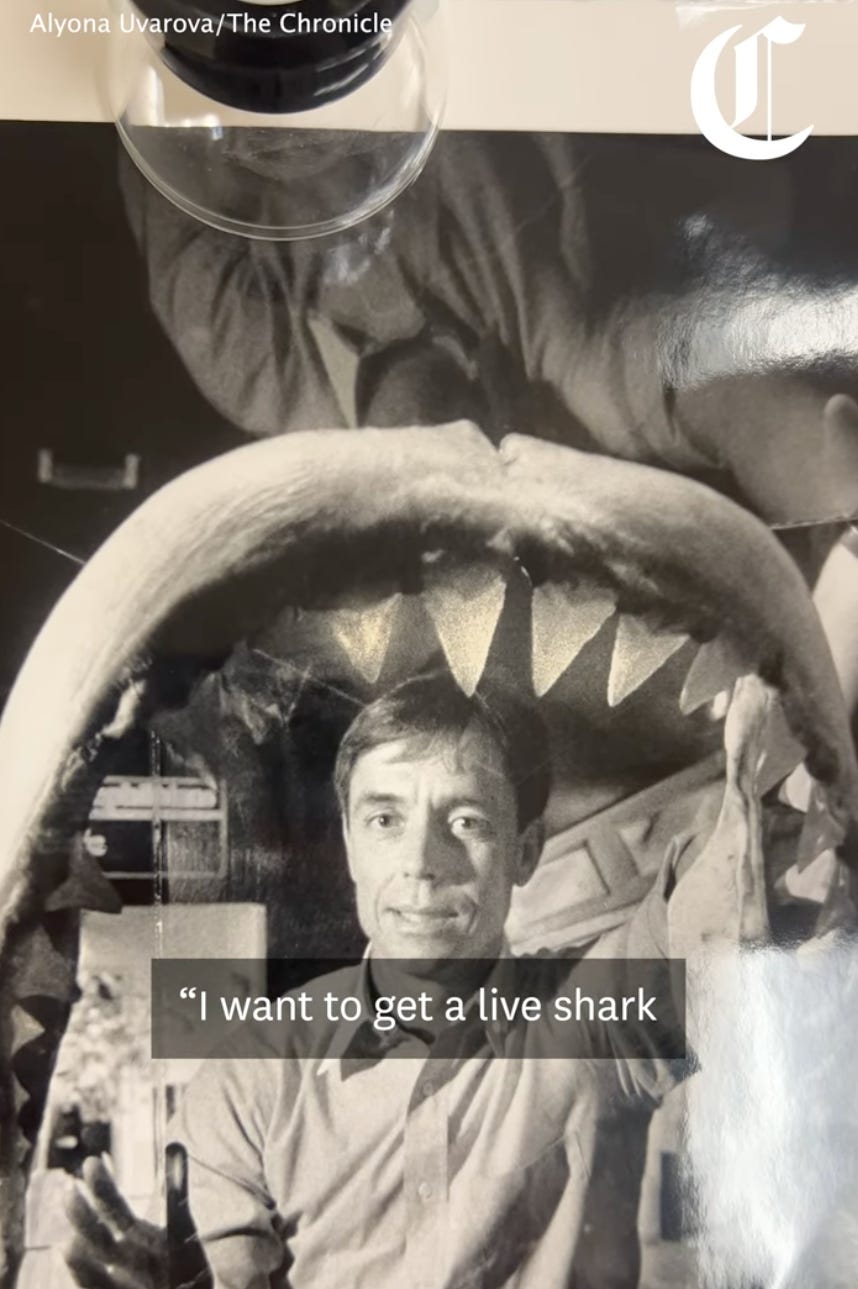

Around 1984, I had an internship at San Francisco’s Steinhart Aquarium under the direction of Dr. John McCosker, the ichthyologist and aquatic biologist. McCosker was a real life Hooper before JAWS, the first trained scientist to ever swim with and study Great White sharks. He and his research team came up with the “bite and spit” hypothesis, that Great Whites first bite and then spit out their prey before feeding. Great Whites might bite humans by accident, he found, but didn’t hunt us. Surfers paddling on short surfboards looked like fat seals from the shark’s POV below, McCosker’s research hypothesized. Attacks were a misunderstanding.

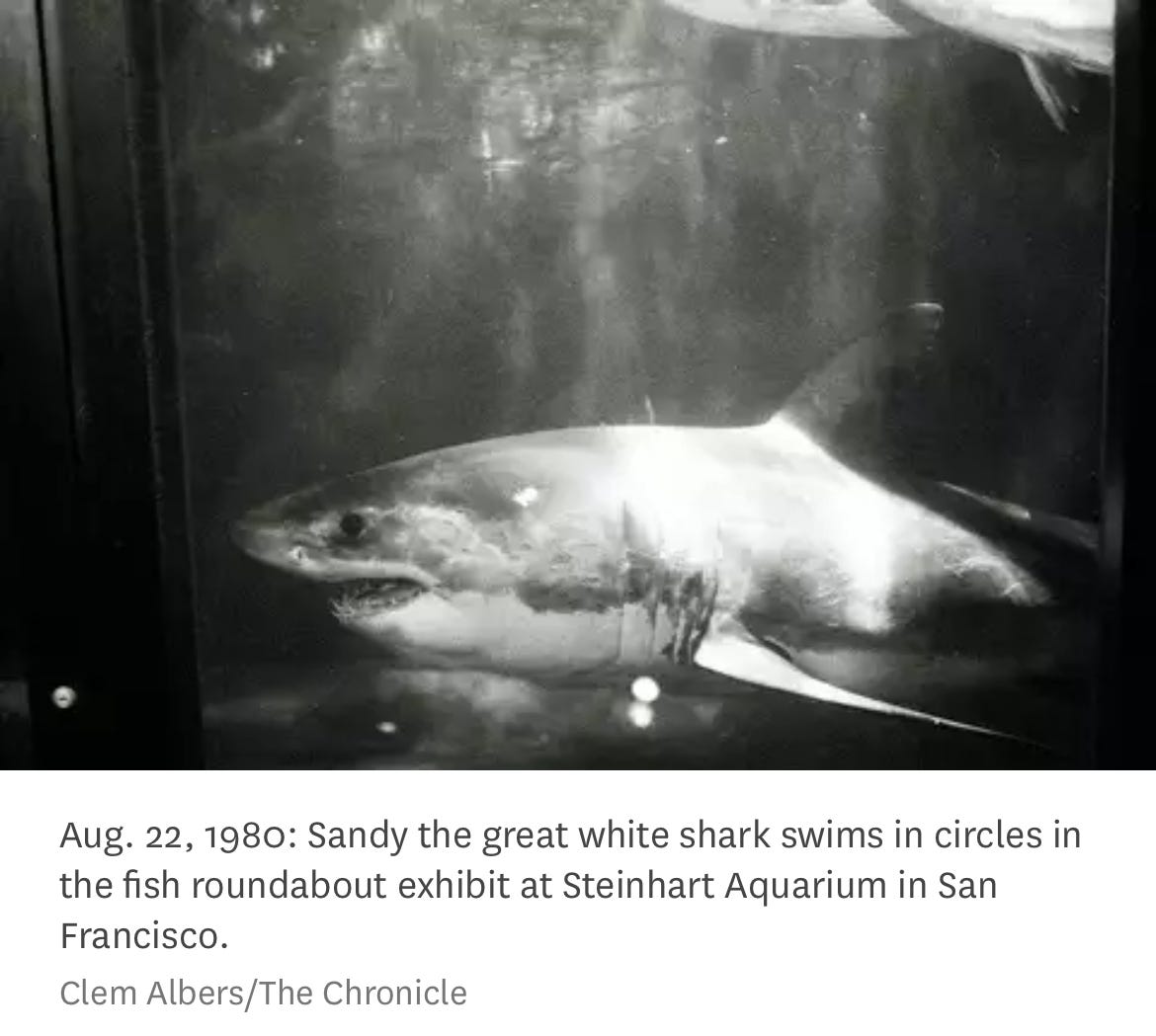

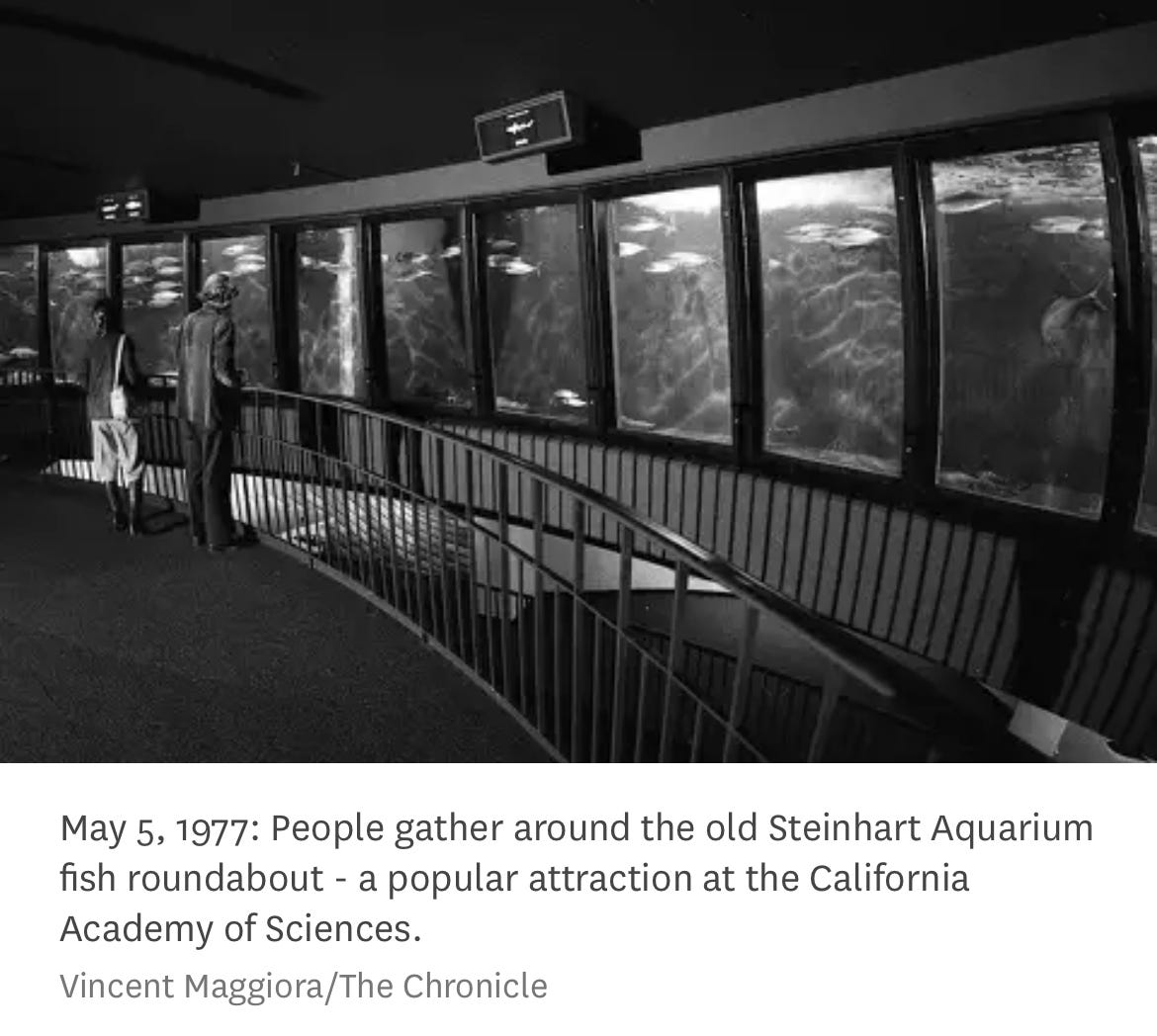

In 1980, McCosker had transported “Sandy,” a six-foot Great White shark caught by a Bodega Bay fisherman, and placed her in the Aquarium’s Fish Roundabout, a donut-shaped tank meant to imitate the ocean’s pelagic zone. Forty thousand visitors came to watch Sandy swim. I was one of them. Sandy looked confused in the bright light of the Roundabout, which glowed like a drive-in movie screen against the dark and carpeted observation platform in the center of the circular tank. McCosker studied Sandy from inside and outside the Roundabout during the five days she was there. Then he tagged and released her out at the Farallon Islands. It was the first time a Great White had been kept alive in an aquarium.

WATCH: ‘Sandy' the Great White shark kept in San Francisco aquarium

When I arrived four years later, there were no Great Whites in the Roundabout but there were some Sevengill and Leopard sharks, both native to San Francisco Bay. I spent most of my internship feeding the depressed Chambered Nautili and other creatures in the small exhibits, mopping endless puddles of water behind the tanks, and defrosting baitfish. But one day McCosker asked if I wanted to clean the glass ON THE INSIDE of the 8-feet-deep, 10-feet-wide Roundabout tank.

“Yes!!” I said, not fully disclosing how little scuba training I really had. I pulled on a wetsuit and walked up the staff stairs behind the tank that led up to top. I had dumped buckets of bait fish in here at feeding time. I practiced a few breaths with the SCUBA tank regulator and adjusted my weight belt. Balanced on the lip of the tank about to slide into the water, I hesitated.

Hmmmm, lots of fish in there. But, it’s got to be safe, right? Those sharks are very well fed. OK, here we go.

I slipped into the water. The weight belt brought me quickly down to the bottom as the water roared past me, filled with fat yellowtail tuna, striped bass, California barracuda, and mackerel. I could feel the current. A five-foot Sevengill shark lazed towards me in the midst of a yellowtail pack, snaggly teeth hanging out of its lower jaw. I held my breath. It paid zero attention to me. A stingray flapped past. It was as if I was standing on the side of a freeway watching cars whiz by. I organized myself next to a pane of glass and began cleaning. Leopard sharks cruised the bottom of the tank like dogs snuffling for debris as I scrubbed the algae off the glass. A little girl standing with her mom on the viewing platform waved to me. I waved back.

From Water to Words

Eventually, I found that I didn’t have the patience for the scientific method. I caught the byline bug writing my first stories about coastal access and fisheries management for the State Coastal Conservancy in Oakland my senior year of college. I started down the journalism road but kept my love of the ocean.

I swim in San Francisco Bay even though I know Great Whites visit here (one was recorded eating a seal off of Alcatraz in October 2015). I also know there has never been a documented shark attack inside of San Francisco Bay.

When I did my first one-mile bay swim in 2014, I discovered that the scariest thing in the water was me, not sharks.

Today, I worry more about close encounters of the pinniped kind than sharks. Seals and sea lions have “played with” and bumped many swimmers I know. Some have been scratched or bitten, requiring antibiotics.

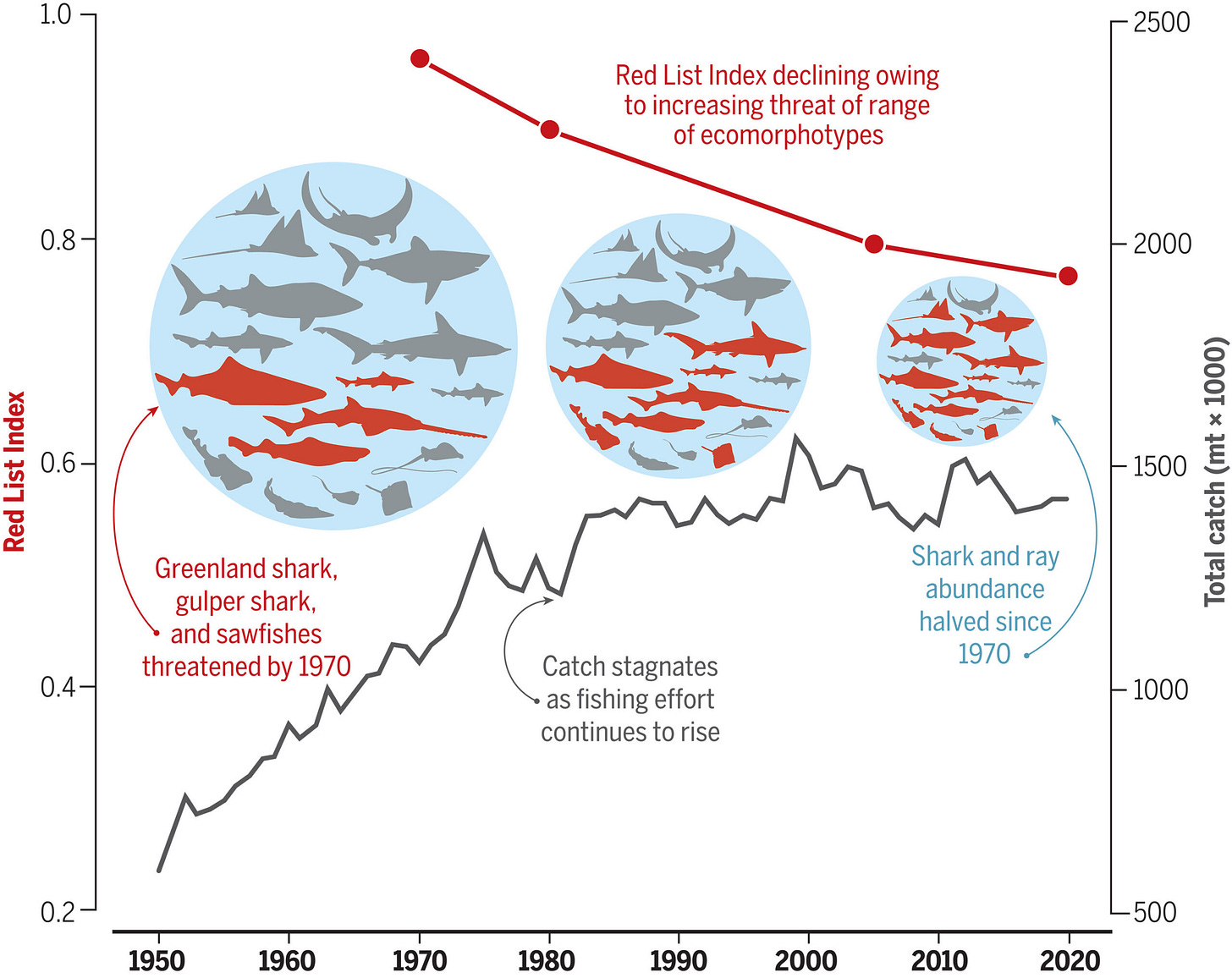

Even if you’re not a would-be marine biologist or an open water swimmer, you should be able to appreciate that sharks have gotten a bad rap from JAWS and are in desperate need of protection from overfishing and finning.

“Sharks are not monsters, they are magnificent,” super-swimmer Lewis Pugh told the New York Post in May after completing a 12-day, 60-mile swim around Martha’s Vineyard (where JAWS was filmed). “JAWS has shaped the narrative about sharks for the past 50 years as cold-blooded killers out to get us, and it’s created a culture of fear around the world.”

Sharks are essential to our oceans’ ecosystem, without them it faces collapse. And with up to 100 million sharks killed each year — that’s 275,000 each day –– this could become our reality. What can we do?

Watch JAWS this summer and then donate to save sharks. Swim in the ocean and know that sharks don’t care about you. Swim or surf with a sharkbanz electromagnetic shark and ray repellant band if it makes you feel safer. Educate the sharks in your mind by learning more about the ones in the water and be grateful for the role these creatures play in our beautiful and fragile oceans.

Compliments, Pia, on tying the Jaws anniversary to both the collective and personal memory. It all flows swimmingly. 🏊♀️

I love your writing Pia! This was so cool to read! Thank you for your writing!